Yves Michel Dumond - French Journalist & Vietnam War Ex-POW

This webpage is very graphic intensive with authentic photos...loading may take some time. Please be patient and allow the page to fully load.

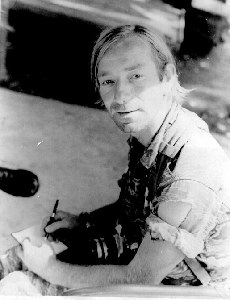

Yves-Michel Dumond

Thanks to Internet, I've had the pleasure of getting to know Mr. Dumond. He has allowed me to share his personal story with you.

Here is the true story of a young French freelance photographer and his time as a POW in Vietnam......

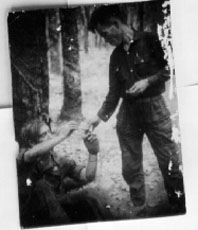

Albert Carlson; Kenneth Wallingford; & Yves-Michel Dumond after their capture.

Pacific Stars & Stripes

Monday, July 17, 1972

HELD 97 DAYS BY REDS

FRENCH LENSMAN TELLS OF CAPTIVITY

Yves-Michel Dumond, 24, a French free-lance photographer, walked out of the jungle about 75 miles northwest of Saigon Thursday. He and two American advisers had been wounded and then captured when the North Vietnamese overran the town of Loc Ninh on April 8. He has not seen the Americans since two days after he was taken captive. This is his story of 97 days as a prisoner.

By YVES-MICHEL DUMOND

SAIGON (UPI) -- We heard the North Vietnamese soldiers making their way down the underground tunnel that led into our bunker. We scrambled out through the sandbagged embrasures and came face to face with an 18-year-old North Vietnamese soldier training his AK47 rifle on us.

Our hands went up. My camera was still in my right hand and I started snapping pictures one-handed. They would have been rare pictures--two Americans with their hands up. But the first thing my captors did was to take away all my cameras and film.

The two Americans and I had been wounded the day before by American jets making strafing runs at North Vietnamese positions right next to us with 20mm guns. They were only flesh wounds but we had not eaten in three days. We were not in very good shape.

They tied us up by the elbows with rubber-insulated electric cord and led us half a mile away to a military press camp. By this time I had identified myself as a "bao chi Phap" (French journalist) but they took more photographs and newsfilm of me than of the other two.

They gave us cigarettes and water. Then we had to walk another six miles or so. We were walking along a level road but the going was very painful because of our wounds and the afternoon sun beating down. We ended up, the three of us, hanging onto the shoulders of the North Vietnamese.

When we got to the next camp the two Americans, whom I knew only as Maj. Carson [his name was actually ~pownet/bios/c/c149.htm"Albert Carlson] and Sgt. Pallingford [his name was actually ~pownet/bios/w/w105.htm"Kenneth Wallingford], were led off for questioning. I was taken before the camp commander, who told me in English, "you are a French journalist, so there is no problem. You will be released." He did not say when.

We were moved to another camp, this time by jeep. It was a captured American jeep and its previous owner, a Capt. Smith [~pownet/bios/s/s189.htm"Mark Smith], was in it. He had a lot of shrapnel wounds, but he kept offering to drive the jeep, because the man doing the driving wasn't very good at it and we were bouncing around a lot.

Smith said he had been wounded and knocked out when a B40 rocket exploded near him. When he woke up he found North Vietnamese standing over him with their rifles pointed at him.

A doctor at this camp gave us penicillin. We were fed the same food our captors were eating--boiled rice, the "nuoc mam" or fermented fish sauce that is the staple condiment of Vietnamese food, vegetables like spinach and squash.

We stayed overnight in a hut. The following evening an officer came and the three Americans were tied up again and led off. They said goodbye to me before they left.

"Don't worry," Smith said. "You'll be back in Saigon in no time. Good luck." We shook hands all around. There were tears in our eyes. It was the last time I saw them or heard of them.

During my three succeeding months in the jungle I never was near a battle. The nearest military action was a B52 heavy bomber strike a couple of miles off. Now and then I could hear jets strafing in the distance.

My captors were members of the North Vietnamese 9th Div., which had led the attack on Saigon during the Tet offensive of 1968. Most of them were North Vietnamese but a number were from the south.

My American-made jungle boots were taken away from me the first day and I was given plastic sandals. The soldiers wore "Ho Chi Minh" sandals with soles cut from tire treads.

I was impressed by their personal cleanliness. They washed twice a day, were clean-shaven and kept their hair trimmed and their nails clean.

I had very little to do. There was nothing to read except a couple of National Liberation Front political pamphlets in English. The soldiers and officers were not very talkative, and they usually spoke to me only in English, not in French.

I ached for something to do. For a couple of days they let me help thread leaves onto bamboo poles for jungle-hut roofs. I did that for two days and those two days passed very quickly. Then they decided I should not be doing any work.

Most of all, I missed the sky. Now and then you can see a sliver of it through towering foliage of the deep jungle. When that happened I would look heavenward by the hour.

I did a lot of thinking, mostly about my past life, and about my mother. She and my father are separated. I have two sisters but I am the only surviving son.

I did a lot of praying, too. I am not a fervent Catholic, but I am a Catholic, when I prayed, a voice kept telling me that I would not be killed by these men, that I would return to Saigon and would see my family again.

Eventually I became so over poweringly bored that I decided to escape. It was quite simple -- two men were assigned to watch me but one was out of sight and the other was busy boiling water. I just slipped away.

Ten minutes after I escaped I regretted it. I was somewhere deep in Cambodia. The nearest Allied troops scores of miles away through impenetrable jungle. It was hopeless.

I had to keep moving. But by the end of the day I was footsore -- I had lost my plastic sandals in deep mud during one of our many moves -- hungry and thirsty. I had leeches all over my body. I came to another Vietnamese camp and surrendered.

[At the time this article was written, Yves-Michel Dumond was advised by the UPI Bureau Chief to avoid speaking about bad treatment he had received after he escaped because of U.S. Families of POW/MIA's & also worries of retaliation against U.S. soldiers still in POW camps. To read what really happened after his escape, read his story below this article.]

They were aware through radio messages that I had escaped, but obviously not upset about it. I was scarcely even rebuked. I settled down in the new camp and life went on as before.

On July 1 the camp commandant summoned me. I don't know what rank he was because the officers wore the same kind of clothing as the enlisted men, without insignia. But he was the only one that ever spoke to me in French.

He asked me about Bastille Day. I said it was the day that marked the beginning of the French revolution. "A people's revolution," he said. "Perhaps you will be free by that day." He asked me to write a letter to the commander of the eastern front for southern South Vietnam, as the North Vietnamcse call the sector around Saigon.

A week later he told me I would be freed, "for the esteem we have for the French and the good relations we have with France."

I had been keeping a diary, but that was taken from me. Then we began making our way back to Vietnam, first along hilly jungle trails, and then through plantation country and finally along an abandoned highway. We moved by night and slept by day in jungle huts or deserted farmhouses.

We went through several villages on bicycles, I sitting on the rear baggage rack. I was told to keep a scarf around my head so the villagers would not recognize me as a non-Oriental and perhaps make trouble.

Finally on Highway 22, inside Vietnam and about 75 miles north of Saigon, we shook hands, my escort officer told me, "when you get back we hope you'll tell the truth. We hope you'll understand that we are fighting for the reunification of Vietnam."

They turned and started back up the road. I walked and walked -- and kept walking. It was early morning. I had gone about 12 miles when I finally saw some Vietnamese civilians on motorbikes coming toward me.

All of them stared at me but half a dozen or so went by before one of them stopped. "Do you want to go to Tay Ninh?" the driver asked, naming the next city to the south. "Yes," I said.

"Good," he replied. "Beaucoup GI in Tay Ninh." I was too tired to explain that I was a French photographer.

I got off at a police post. They radioed for an American medevac helicopter. A few minutes later I was in the U.S. Army hospital at Lung Binh, just northeast of Saigon.

They told me I have malaria, which doesn't surprise me. I also have to have the shrapnel taken out of my left bicep and thigh. I haven't decided yet whether to stay in Vietnam.

____________________________________________________________________________

Yves-Michel Dumond during captivity.

Michel is now free to give details.....

After the loss of Dien Bien Phu on May 7th, 1954 at 17.30 p.m., 11,721 men had been captured by the North Vietnamese Army. Only 3,290 came back from the POW camps. 7801 are missing.

Of course, a lot died during their captivity but still, the French government has done nothing to try to explain this big lost. I think they were too busy to keep what was left from Indochina.

It has been the same with the Algerian war.

When I was captured with Zippo (~pownet/bios/s/s189.htm"Mark Smith), I know that the French government had some talks with Hanoi through China. I have a uncle who was general in the French army at that time who did a lot to find out what my situation was and to find out if I was still alive or dead. He kept good relations with one of his former Vietnamese officer's, during the Indochina war, who left the Vietnamese army to join the Vietcong army. It looks like the guy that gave to him some information about me. He told my family that I was alive and I should be released very soon.

Light and freedom was reason for me to try to escape. I did it after being there for one month, but it was in vain. I think I was near Kratie in Cambodia. Running in the jungle, and having been wounded after Loc Ninh battle, I got a pine needle through my foot and I had to give up. Running away from them was so great. I managed to do it just for 2 days, but for me it was a great deal. Just to show them I was not a broken person. After that they brought me back to the camp where I had escaped from.

I had a lecture from my guards saying that they had to go to the front because they didn't do their job properly. They started to dig a hole like a tomb. They covered this hole with timbers and mud. With my legs and arms chained, I stayed there for one and half month. Above me they installed a hammock and a plastic sheet and my new guard was spending most of his time in the hammock. When I got out of this place I could not walk. I was like a dog and I still had a chain on my leg.

I remember that I had asked to go to have a piss (urinate) and my guard said "go" and he showed me where to go. He was holding a chain still attached to my right leg while I was crawling just like a dog because I could not walk properly after this time spent in this hole. It was the beginning of the raining season and on the botton of my hole had water and my arms & legs were chained. My extremeties were stuck. I asked my guard, "Why do you have this chain still attached to my leg?" and he replied, "We know you still want to escape again.". I replied, "Look at me and how do you think I can escape again like I am?"

They were awful. That was the hardest time of my life to be just like a dog; held by somebody when I could not even stand up on my feet.

I was in that hole for about 1 1/2 months.

At that time my mother had this message from my uncle that I had done something very, very bad and I would not be released soon.

No more information from my uncle's "friend" came until I was released on the road between Krek (in Cambodia) and Tay Ninh. I walked on this road (I had been lucky not to hit a mine), until I was stopped by soldiers from the South Army. They radioed the United States Headquarters, because they thought I was an American soldier. Then after some time 5 choppers came to pick me up, we flew to Laike then to Bien Hoa hospital for a debriefing. I then went to Grall hospital in Saigon where I stayed 4 months.

I had malaria; shrapnel still in my body; was anemic (my red blood count was 2.5 million, normal is 4.5-5 million); and had lost 15 kilos. I also had a kind of beri beri.

During my captivity, I was always alone and didn't see any U.S. soldiers.

So, this is my story as a freelance photographer in Viet Nam.

____________________________________________________________________________

Zippo (Mark Smith) & Howard Lull

Michel recalls Mark Smith....

I met him a few months before Loc Ninh battle and became good friends. We spent some time together in Saigon and in Laike. One day I got a message from Zippo (I always call him Zippo), that I should come to Laike because something very interesting as a photographer, will happen around Laike.

As soon as I got this message, I went to Laike and met Zippo. He told me that a lot of activities happen around Loc Ninh and the intelligence had spotted some tanks. So as a photographer, I asked the press department of the South Vietnamese Army for authorization to go to Loc Ninh. This authorization was not accepted and I went to meet Mark and told him what the South Vietnamese PR told me. His reply was, "Don't worry, Frenchie (he use to call me always like this and even for his last radio message from Loc Ninh was: We are all wounded, I'm destroying the radio and Frenchie is with us), comes with me." We did the journey in Zippo's jeep.

We stopped at An Loc to met his girl friend and then we took the road to Loc Ninh. We knew that this part of the road from An Loc to Loc Ninh was very dangerous. I was sitting on the front passenger seat jeep and Zippo gave to me a B40 (launch grenade propeller.) -I hope this is the right word- and told me if we have to use it just use it.

We reached Loc Ninh base without any problems. We didn't meet anybody on the way to Loc Ninh, and Zippo told me to go to the U.S. adviser bunker because he heard that the South Vietnamese Commander knew I was there and he wants to fly me back to Laike. So I just hide myself in this bunker until darkness arrived and the helicopter left the base. Then we had this farewell party for Albert Carlson. His wife was waiting for him in Bangkok.

Next morning the battle of Loc Ninh started around 5.45 PM.

Michel recalls a funny story.....

During the battle at Loc Ninh, Zippo (Mark Smith) was directing the military operation (using the radio I went to pick up inside the bunker where we spent our last night drinking beers for Carlson's farewell party) and at one stage, the operation control told him that there was a big concentration of VC near the house of the French farmer (Mark & I had drank wine with this French farmer the day before the attack.) Mark sent this message to the Airforce HQ, "Destroy the French house and the swimming pool." And I told Mark, "Don't do that! You know that he has a cellar full of French wine under his house!"

SAN FRANCISCO (UPI)

A returned war prisoner has credited a free-lance photographer working for UPI with saving his life when he was captured in Vietnam.

Maj. Albert Carlson, among the former captives returned to the U.S., Friday, praised the photographer's first aid work at Loc Ninh. Carlson's wife, Nancy, speaking to newsmen at Letterman Hospital where Carlson is staying, said "he feels he owes his life" to the French photographer Yves Michele Dumond who was working for United Press International when he and Carlson were captured on April 7, 1972.

Dumond was released earlier.

**It is with great sorrow to report that it was learned on September 20, 1999, that Albert Edwin *Ed* Carlson passed away last month from cancer...**

As we shared some hard times together, some deep relations have been built between us even if I spoke to him only once after he was released. He was a companion of a short part of my life who will never disappear from my brain, my skin.

He survived Loc Ninh...

Yves-Michel Dumond